Key Takeaways

- Different roles: Some insulins cover meals, others cover background needs.

- Timing matters: Onset, peak, and duration guide how insulin is used.

- Names can confuse: Brand and generic labels often mean similar categories.

- Devices vary: Pens, vials, and needles affect day-to-day routines.

- Plans are personal: Your clinician matches insulin to your goals.

Sorting through types of insulin can feel like learning a new language. Many people are trying to match a prescription name to what it actually does. Others want to understand why one insulin is taken with meals, but another is not.

You’ll find clear categories, timing basics, and practical examples below. The goal is to help you feel more confident during conversations with your diabetes care team.

Types of Insulin: Timing, Roles, and Examples

Insulin is often grouped by how quickly it starts working and how long it lasts. Those timing patterns help explain “why this one at meals” and “why this one once daily.” Many plans use a combination, such as a background insulin plus a mealtime insulin.

You may also hear insulin described by its role. A “basal” product supports background needs between meals and overnight. A “bolus” product supports rises in glucose after eating. These roles can apply across multiple product names.

Another helpful split is human insulin versus insulin analogs (lab-modified versions of insulin). Analogs were developed to better match real-life needs, such as faster mealtime action or steadier all-day coverage. Your clinician may choose between these based on patterns, lifestyle, and safety considerations.

For a high-level view of diabetes treatment principles, read the ADA Standards of Care in the context of individualized goals.

Insulin Onset, Peak, and Duration: A Practical Timing Map

Most insulin instructions make more sense once you know three timing terms. Onset is when glucose-lowering effects begin. Peak is when the effect is strongest. Duration is how long meaningful effects may last.

A types of insulin chart can be a useful shortcut, but it is still a simplification. Timing varies by product, dose, injection site, temperature, activity, and illness. Even the same person may notice different day-to-day patterns.

Use the table below as a general reference, not a personal schedule. Your care team may tailor timing based on glucose data, meals, and hypoglycemia risk.

| Category (common label) | Typical onset | Typical peak | Typical duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid-acting (mealtime) | Minutes | About 1–2 hours | Several hours |

| Short-acting (regular human) | About 30–60 minutes | About 2–4 hours | Up to several hours longer |

| Intermediate-acting (often NPH) | Hours | Midday peak is common | Roughly half to full day |

| Long-acting / ultra-long (basal) | Hours | Minimal or “flat” peak | About 1 day or longer |

| Premixed blends | Varies by mix | Often two peaks | Varies by mix |

Note: Product labels list specific timing ranges and handling details. If timing seems “off,” it may be technique, storage, or changing insulin needs.

Basal Insulin vs Bolus Insulin in Daily Plans

Basal insulin is commonly used to cover the glucose your body releases between meals and overnight. This is sometimes called “background” coverage. People may use it in type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes, especially when fasting numbers are above target.

Bolus doses are intended for meals and sometimes for high readings. They may be used with carbohydrate counting, a correction factor, or a structured plan created with a clinician. Many people do best when bolus dosing is linked to meals, rather than used as a “catch-up” strategy.

Daily plans can look different while aiming for the same goal. Some people use a basal-plus approach (basal insulin plus one mealtime dose). Others use a full basal-bolus approach (basal insulin plus mealtime doses). When you want more background on options, the 5 Types Of Insulin article helps compare categories in plain language.

If you’re also sorting general diabetes resources, browsing Diabetes Topics can help you find related education in one place.

Rapid-Acting Options for Meals and Corrections

Rapid-acting insulin is designed to work quickly around meals. It’s often used to cover carbohydrate intake and to address out-of-range glucose values using a clinician-defined method. Common examples include insulin lispro, insulin aspart, and insulin glulisine.

Even within one category, products can behave a little differently. Food timing, injection site, and activity can change how fast it seems to work. Some people see stronger effects after exercise, while stress or illness can reduce sensitivity.

It also helps to know what “rapid” means in real life. It usually starts faster than regular human insulin, but it still requires planning. For a deeper breakdown of timing and common use cases, learn more in Rapid Acting Insulin for meal-dose context.

Glucose monitoring supports safer adjustments over time. Many people use finger-stick checks or continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) trends to see whether a chosen strategy is matching meal patterns.

Short-Acting Insulin and Regular Human Insulin

Short-acting insulin usually refers to regular human insulin. It tends to start working more slowly than rapid-acting options. That slower onset can affect when it is taken in relation to meals.

Regular insulin may be used for mealtime coverage in some treatment plans. It may also appear in hospital protocols and structured outpatient regimens. Because its peak can arrive later, late hypoglycemia may be a concern for some people.

If you are trying to understand timing differences and typical scenarios, the article on Short Acting Insulin explains how it is commonly positioned. It can also help to compare patterns using your own glucose logs, rather than relying on a “one-size” chart.

When people talk about the “regular” option, they may mean the human insulin type, not a routine schedule. Clarifying that wording can prevent mix-ups during visits and pharmacy refills.

Intermediate Options: NPH Insulin and Premixed Mixes

NPH insulin is an intermediate-acting product that has been used for decades. It is often described as “cloudy” because it is a suspension. That look is expected for NPH, but it can be surprising if you are used to clear insulin.

Intermediate-acting insulin can have a more noticeable peak than many long-acting options. For some people, that peak helps with daytime coverage. For others, it can increase the need for careful meal timing and glucose checks.

Premixed formulas combine two insulin components in one product. Many mixes pair an intermediate component with a faster component. This can reduce the number of injections, but it may also reduce flexibility with meal timing.

If you want a clearer explanation of intermediate patterns and common pros and cons, read Intermediate Acting Insulin for practical context. That overview can help you ask better questions about fit and trade-offs.

Sliding Scale and Correction Doses: What Those Terms Mean

Sliding scale insulin usually means giving a set dose based on a current glucose reading. It is often written as a table, such as “if glucose is in this range, take this amount.” Some people encounter sliding scales after a hospital stay or during short-term changes in routine.

In everyday life, many clinicians prefer structured approaches that consider meals and insulin sensitivity. You may hear “correction dose” used for extra insulin meant to bring down a higher reading. The key is that correction plans are typically individualized and should align with your overall regimen.

Using reactive dosing without a plan can raise the risk of “stacking,” where doses overlap. That overlap can contribute to unexpected lows later on. If sliding scale insulin is part of your instructions, it is reasonable to ask how it fits with meals, activity, and other insulin you take.

For broader support articles on living with insulin in type 2 diabetes, browsing Type 2 Diabetes can help you find topic-based reading. For product and therapy categories, Type 1 Diabetes Options can be a starting point for comparing what’s commonly discussed.

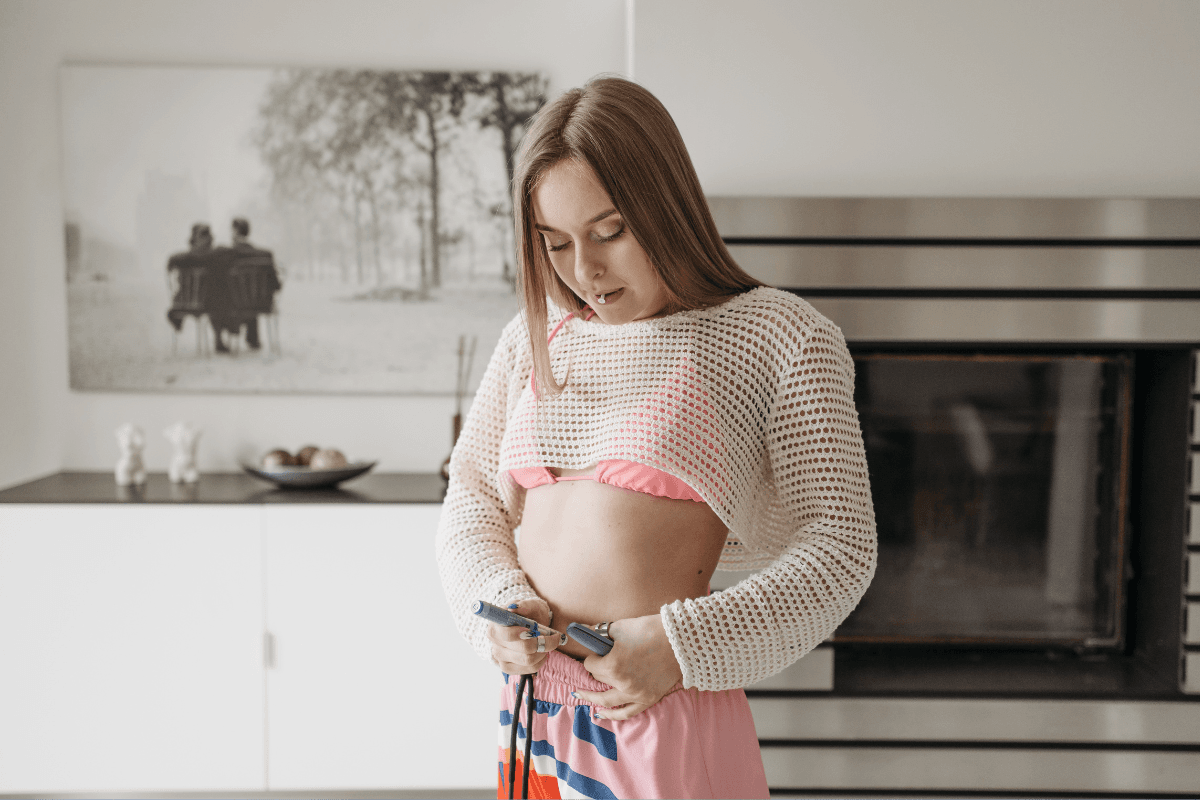

Pens, Needles, and Injection Technique Basics

Insulin can be delivered by vial and syringe, pen devices, or pumps. Pens are popular because they are portable and can feel simpler to use. Some pens are disposable, while others use replaceable cartridges.

Device choice can affect adherence, comfort, and dosing confidence. People with vision changes or hand arthritis may prefer a pen with an easier dial. If you want a device-focused overview, read Types Of Insulin Pen for what to compare and why.

Needles also matter for comfort and consistency. Many people use short, fine pen needles, but the “best” option depends on body type and technique. If you’re trying to understand needle formats and compatibility, you can see examples like BD Nano Pro Needles for basic specs and sizing.

Tip: Never share pens or needles, even with family members. The FDA’s insulin pen safety guidance explains infection risks in plain terms.

Comparing Long-Acting Choices: What Names Signal

Long-acting insulins are intended to provide steadier background coverage. Some are labeled “ultra-long” because they can last beyond a day for many people. Your clinician may choose a long-acting option based on glucose patterns, daily routine, and how predictable the action needs to be.

When you see long-acting insulin names, you’ll often notice repeating patterns in the generic names. For example, insulin glargine, insulin detemir, and insulin degludec are all basal options. Brand names like Lantus, Levemir, and Tresiba refer to specific versions and devices.

If you’re learning the basics of how long-acting products are commonly used, Long Acting Insulin can help you compare expected roles. If you are also comparing pen formats and what they look like, seeing a device example such as Lantus SoloStar can make the terminology feel more concrete.

It’s normal to have questions about switching, missed doses, or variable schedules. Those situations are important to discuss with a clinician, because safety depends on the full regimen and your glucose trends.

Recap

Insulin categories are built around timing and purpose. Meal-time options act faster, while background options aim for steadier coverage. Intermediate and premixed products can be useful but may require more structured routines.

Bring your insulin list, device type, and recent glucose patterns to visits. Clear questions lead to clearer plans, especially when routines change.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice for your personal situation.